Group Sound Changes the Chemistry of Loneliness

There is a kind of quiet that doesn’t feel peaceful.

It’s the quiet that settles when you’ve gone too long without being around another person.

Your body feels heavy.

Time seems slower.

Even small noises start to sound sharper.

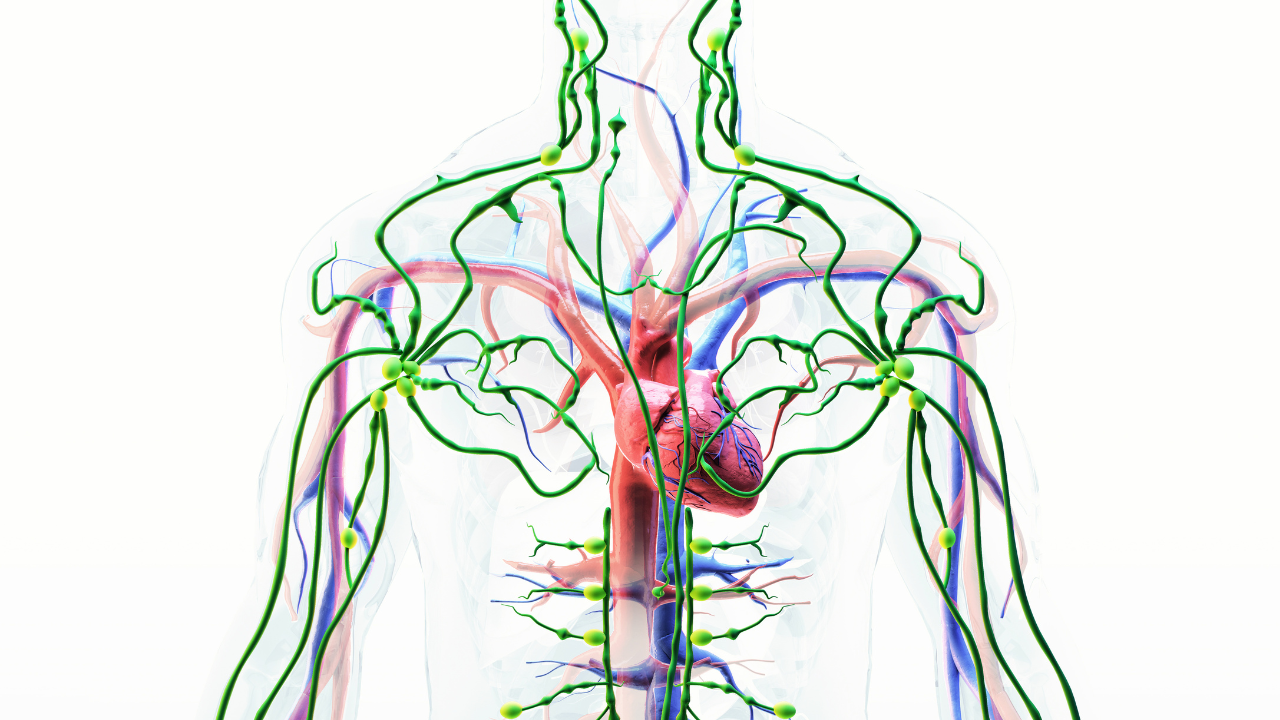

Loneliness isn’t just emotional. It changes how the body works.

When you spend too much time without social connection, stress hormones stay elevated.

Blood pressure rises. Inflammation increases.

The body starts to behave as if it’s defending itself.

That defensive state affects how the heart, brain, and immune system communicate.

The longer it lasts, the harder it is for the nervous system to shift back toward balance.

But the same biology that responds to isolation also responds to sound.

Especially shared sound.

How Sound Begins to Change Chemistry

When people sing, hum, or even breathe in rhythm together, measurable changes appear within minutes.

Cortisol drops.

Endorphins rise.

Heart-rate patterns begin to move toward a common rhythm.

Research on group singing shows that these changes are not psychological tricks. They are shifts in hormone and nervous-system activity that can be recorded and replicated.

A 2024 analysis by Ozaki and colleagues found that group vocalization consistently improves heart-rate variability, a key marker of vagal tone and emotional regulation.

Earlier studies by Pearce and Launay at Oxford showed that synchronized singing and movement increase pain threshold and social bonding through endorphin release.

The body, it seems, is built to respond positively to rhythm shared with others.

The Vagus Nerve’s Role in Connection

Each sound you make travels as vibration through the chest, throat, and ear canal.

Those vibrations activate branches of the vagus nerve, the same network that coordinates heart rhythm, breathing, and digestion.

When another person’s voice joins yours, the vagus picks up those external vibrations too.

Now your internal and external signals begin to interact.

Your breathing adjusts. Heartbeats become slightly more variable.

Tension in the shoulders and jaw begins to soften.

Researchers call this process interpersonal physiological coupling.

It describes how people’s bodies synchronize through shared rhythm and sound.

In choirs, these changes are easy to measure.

During group singing, heart-rate patterns often align almost perfectly from person to person.

It’s a form of communication that happens below words.

A Practice for Reconnection

You do not need a choir to experience this.

You only need one other person willing to make sound with you for a few minutes.

Try this small experiment.

1️⃣ Sit nearby.

You can face each other or sit side by side.

Take one easy breath together.

2️⃣ Hum on the exhale.

Keep the tone low and steady.

Feel the vibration move through your chest and into the air between you.

3️⃣ Listen for overlap.

Let your sounds blend naturally.

There is no need to match pitch or volume.

Notice the small waves of sound that seem to fill the space.

4️⃣ After about a minute, stop together.

Sit quietly for thirty seconds.

Notice what changed.

Your breathing might feel slower.

The air may seem thicker or warmer.

You might feel a quiet pulse that wasn’t there before.

This is the body’s chemistry adjusting.

Shared vibration activates the vagus nerve and increases heart-rate variability.

Those are signals of improved regulation and recovery.

How It Works

The act of humming sets off gentle pressure waves through the chest and vocal tract.

These waves stimulate mechanoreceptors that feed into the vagus nerve.

That signal tells the brainstem that breathing is slow and safe, which lowers sympathetic activity.

At the same time, the rhythmic overlap of two voices provides a steady external pattern for the nervous system to match. The combination of internal and external rhythm promotes synchronization in both people.

Heart rhythm, respiration, and even micro-movements begin to align.

In this synchronized state, the body releases small bursts of endorphins and oxytocin.

Both are linked to social comfort and reduced pain sensitivity.

That chemistry makes connection feel easier and more rewarding.

It is not about creating music.

It is about giving the nervous system a reference point for balance that includes someone else.

Why Repetition Matters

The first time you try this, the change may feel subtle.

But the nervous system learns through repetition.

Each time you hum or breathe in rhythm with another person, the vagus nerve strengthens its pattern of response.

The body becomes faster at shifting out of isolation and back into a state of shared regulation.

Regular practice can gradually raise baseline heart-rate variability and lower resting cortisol levels.

Those shifts correlate with better sleep, faster recovery from stress, and a greater sense of ease in social situations.

Over time, the chemistry of loneliness begins to change.

Instead of reacting to others as potential stressors, your body starts to expect coordination. It learns that being around people is not a drain on energy but a source of balance.

What to Notice

With time, you may notice that your responses to social situations shift.

Crowds feel less tiring.

Conversation feels easier.

Moments of silence with others feel comfortable rather than awkward.

These are signs of a recalibrated nervous system.

Physiology catching up to what emotion already knows: that connection is restorative.

Every shared hum, tone, or breath is a small act of repair.

The chemistry of loneliness dissolves one vibration at a time.

Be well, Jim

References

-

Bowling, D. L., Garda-Persichini, E., Atarama, M., Loconsole, M., Zoppetti, N., Baader, N., … Hoeschele, M. (2022). Endogenous oxytocin, cortisol, and testosterone in response to group singing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 847726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.847726

-

Good, A., & Russo, F. A. (2022). Changes in mood, oxytocin, and cortisol following group and solo singing. Psychology of Music, 50(8), 1970–1988. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211042668

-

Pearce, E., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2015). The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Society Open Science, 2(10), 150221. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150221

-

Tarr, B., Launay, J., Cohen, E., & Dunbar, R. (2015). Synchrony and exertion during dance independently raise pain threshold and encourage social bonding. Biology Letters, 11(10), 20150767. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0767

-

Wang, F., et al. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 90 cohort studies on social isolation, loneliness and mortality. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 1463–1475. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01617-6